All Nonfiction

- Bullying

- Books

- Academic

- Author Interviews

- Celebrity interviews

- College Articles

- College Essays

- Educator of the Year

- Heroes

- Interviews

- Memoir

- Personal Experience

- Sports

- Travel & Culture

All Opinions

- Bullying

- Current Events / Politics

- Discrimination

- Drugs / Alcohol / Smoking

- Entertainment / Celebrities

- Environment

- Love / Relationships

- Movies / Music / TV

- Pop Culture / Trends

- School / College

- Social Issues / Civics

- Spirituality / Religion

- Sports / Hobbies

All Hot Topics

- Bullying

- Community Service

- Environment

- Health

- Letters to the Editor

- Pride & Prejudice

- What Matters

- Back

Summer Guide

- Program Links

- Program Reviews

- Back

College Guide

- College Links

- College Reviews

- College Essays

- College Articles

- Back

The Girl In the Dark Blue Coat

Somewhere in the dullness or wartime Berlin, in a small courtyard on a street called Miricale Strasse, was a girl in a dark coat. Her age was undeterminable, for she was both young and old. A child and a woman. Somewhere in the gray space between. Her coat – the color more navy than black – had not always been hers. It was quite evident. For one, it was a man’s coat. For another, it was much too big. The sleeves swallowing her arms and the hem drifting past her knees. She was a small, pale shape inside it. Her face like plaster. Her eyes like a crumbled building. She wore no smile. Underneath her great coat, near her heart, she clutched a hat box.

Four days prior, the girl had arrived on Miricale Strasse with a mind on miracles. She did not believe in such things and had found herself doubtful that the street held a share of them as its name suggested. Miracle Street. What irony, she had thought. What hideous irony.

There were no miracles in the Third Reich.

There was, however, a woman on the third floor of the apartment at the corner that was known to hide people of “dire circumstances” for a few days. When the girl had arrived at the apartment’s door for the first time, she had been panting from the speed of which she ascended the stairs and dripping with the rain she had carried in from outside. She had felt the eyes – the real kind or the ones that stalked her like shadows on her dreams she did not know – of someone following her from the moment she stepped off the S-Bahn near the Zoo, and had worked herself into a mess of anxiety. Trembling, she had knocked with the means to use force, only to pause right before her knuckles hit wood so that the impact was a soft, almost inaudible tap.

The woman that answered was younger than expected. She had a delicate kind of face meant for tea parties and polite conversation, if only it wasn’t for her nose which stood prominently out from her face like the beak of a tropical bird. She had not look surprised to see the girl standing in the hallway.

The first things that had come out of the woman’s mouth was, “Get in here, you draft idiot. I’m neither fond of nor looking forward to capital punishment.”

The second – after the girl was inside the apartment and the door was securely closed – was, “Do not tell me your name. Names are dangerous in this trade. If you need something to call me by, call me Auntie. I won’t bother with the same because you will be gone soon enough.”

The woman had ended the introduction, thirdly, with a joyous rant about National Socialism with phrases like “whimpering babies with swastika nappies” and “our great and idiotic leader.”

The girl had liked the woman immediately and immensely.

The woman who would soon be called Auntie had fed her a meager dinner of boiled potatoes – not because she was poor but that was all that was to be had in wartime Berlin – and gave a majority of her portion to the girl. Half-way through the girl had softly sat her fork down and closed her eyes. She had been tired, exhausted really. She could not remember the last time she had felt awake. Anymore she was a beating heart, a poster on a street corner with the words, “ENEMY OF THE REICH,” a pair of shoes with soles so worn that she could feel the grit on the pavement as she walked, and an instinct to bolt at an unknown knock at a door. When the girl had opened her eyes once more it was as if she was looking up from some great depth – like looking up from a grave. A grave of which there was other bodies with her, lying on top and beside and beneath. They were so heavy. How easy it would have been to just let their weight smother her like a warm blanket.

She had told Auntie a secret, and the woman gave her a hanger.

“Miracle Street,” the girl had laughed bitterly.

Auntie had quickly rose to clear the table of its chipped china and turned her back at the sink so the girl could weep unwatched. Once enough time had passed, the woman wiped her hands on her skirt and faced the girl. She had an anger burning through her eyes.

“You will survive this,” she had said. “You will survive tonight. This endless war will end. Hitler is just a man, and he will bleed before all this is over. But you will survive. You have to. Survive to tell the rest of the world why someone as seemingly insignificant as you matter. Tell your story and the world will hear it.”

The girl held a hand to her stomach. “And what if I can’t?”

“You will,” said Auntie.

“But—”

“You will.”

The girl would have to wait for the bombers to come, for that would be the only time she could go out onto the courtyard confident that she would be undetected. Not even the state police bothered with identity papers when the bombs were falling. On the forth night, the girl had watched the planes arrive like silver birds against a cloudless sky. Air-raids sirens screamed and all of Berlin retreated to cellars and shelters with the solemn disposition of a herd of sheep. Mothers with their gaggle of children. Young boys with playing cards stuffed in their pockets. Old men that would spend the next few hours drinking peach brandy and gabbing about their own war days.

But the girl was out in the courtyard, under a bright, full moon, and shivering in her coat.

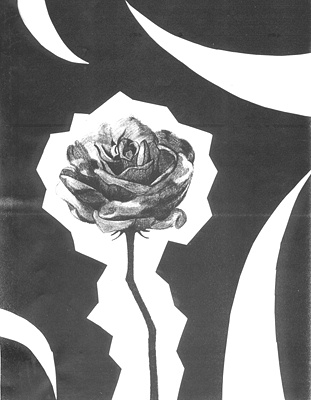

There was a rosebush – a shriveled brown thing that perhaps once had been beautiful – under a string of yellowed laundry, and the girl thought of the roses her mother used to grow in their own courtyard. It was what encouraged her to dig the grave there. As the giant crack of buildings falling apart sounded somewhere quite close and somewhere far away, she would bury the hat box and cover it with dirt. When she was done, the girl would sit back and watch the planes pass overhead and move away, empty of their cargo.

It was quiet on Miricale Strasse once more.

Similar Articles

JOIN THE DISCUSSION

This article has 3 comments.

3 articles 0 photos 13 comments

Favorite Quote:

"Nearly all men can stand adversity, but if you want to test a man's character, give him power."