All Nonfiction

- Bullying

- Books

- Academic

- Author Interviews

- Celebrity interviews

- College Articles

- College Essays

- Educator of the Year

- Heroes

- Interviews

- Memoir

- Personal Experience

- Sports

- Travel & Culture

All Opinions

- Bullying

- Current Events / Politics

- Discrimination

- Drugs / Alcohol / Smoking

- Entertainment / Celebrities

- Environment

- Love / Relationships

- Movies / Music / TV

- Pop Culture / Trends

- School / College

- Social Issues / Civics

- Spirituality / Religion

- Sports / Hobbies

All Hot Topics

- Bullying

- Community Service

- Environment

- Health

- Letters to the Editor

- Pride & Prejudice

- What Matters

- Back

Summer Guide

- Program Links

- Program Reviews

- Back

College Guide

- College Links

- College Reviews

- College Essays

- College Articles

- Back

Mercy

It was one of those life-changing moments, you know? The kind you carry with you through the halls, sure every eye is on you and that they know. The kind that you could talk about for years, except people get tired of hearing it. People always ask for personal information, they think they want it. Then they get it and they run to safer, less emotionally involved pastures. I was that; rather that was me.

I wasn’t always on the move. I remember when I was six, a red building. In the memory I know it’s mine, because the man at the door smiles at me with his white, white teeth and holds the door with his white, white hands. But soon after he left, we did too, and the red building and blue sofa and harsh light stayed six years old.

Not that we don’t have a house, we do, and it’s been the same one for years, we’re not one of those families that treat moving as an annual tradition. Maybe it’s that the big house has a chilled, for-sale feel. My friends, the ones with heated, neat houses—even the ones with weird, stark, modern things—avoid my house like opposite magnets, sliding around each other. Honestly so do we. Kylie never sleeps here anymore; she’s at Ryan’s, or a friend’s, or curled in her car. Anywhere-but-home is her motto, that and just-until-Swarthmore. Just until Swarthmore will she put up with Mom. Just until Swarthmore will she work this sucky job. Just until Swarthmore, then I get her space.

Dad’s starting to ask me about colleges now. I threw him with a laugh and a smile and I ran outside. The leaves were tossing their heads at his stupidity. I wasn’t going to college. College involved quasi-adult experiences and seizing opportunities. I’ll fly to Europe and become a model-- a beautiful, calm, sophisticated girl-about-town. I would have scene. I would laugh at my sister at her little college but support her unconditionally because models have grace. My parents could visit me in my Parisian garret and think privately how they always knew I was unhappy sleeping in a sweater.

Dad had other plans. With the branches shaking their fingers at him, he pulled me back to the kitchen and asked about my preferences. Telling him I wanted to go to the College of Life was not a smart move, and then, just as things were looking iffy, my phone came alive, sounding a retreat. What’s up now, Dad? I’ll see you later.

Downtown the buildings kind of peel away from the sidewalk in a way those tourists never seem to comment on. It must not be beautiful.

Spizzo and Grant had sent out one of their emergency blasts, which worked fine for me even though it meant I would be doing some fast talking. Jesus, the two of them needed a profession for troublemaking. Maybe politics? But that’s such a clichéd answer, and as a nonconformist-- probably clichéd-- teenager, I refuse it.

I pulled up in front of a dime-a-dozen pizza parlor and spent five minutes parallel parking. Driving has saved my life but parking…it’s like a mental block. Kylie says it gets easier once you hit seventeen but I find that unbelievable.

Grant is shifting his elbows around the counter, probably looking for a greaseless spot, and Spizzo is spread over a booth, teasing a waitress with his half-smile.

“Hey Spizzo, if there’s an emergency I don’t think you have time for sex,” I called to him as I twitched my eyebrows at Grant. Giandominico Spiezzo: Spizzo when he’s with us or online, and especially around girls. He’s got me trained like a puppy.

He flashed the girl another smirk, bounded up from the seat and came over. “Merce, so kind of you to help us with this little problem.”

Grant wiped his hands on his jeans and looked me full in the face. “Seriously, Mercy, even you may not be able to fix this one.”

Sighing, I heaved my leather bag onto a stool and pulled out my French subjunctive study guide. “Well, let me know when you want to spill your beans. Thanks for the rescue, though, timing impeccable as always.”

Both guys leaned in simultaneously, like a movie, and Spizzo whispered, “We accidentally stole something.”

I blew my breath out my upper lip in exasperation. “Wanna tell me how that happened, Spizz? Somebody plant it on you? What was it?”

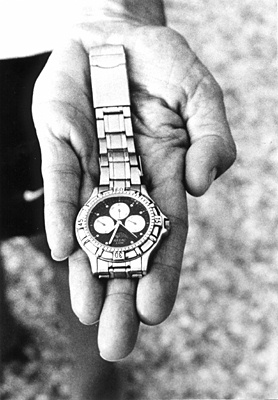

Grant procured a watch from an inner pocket. I took it gingerly, expecting it to feel hot to the touch, and placed it in front of me. Spizzo handed me a price tag, one of those useless string ones that fall off when you touch them.

“We’re at the Standard sidewalk sale and on one of the tables is this watch.” Grant gestured to my French homework. “Spizzo picked it up, and we examined it thoroughly for a price tag or something, found nothing. So we asked someone, who also looked at it and said if there’s no tag it’s not theirs. SO—we pocketed it and came here for food. Which is when Spizz found the price tag caught in his sleeve.”

The tag in my hand read one hundred and twenty dollars. “So really this is a moral dilemma,” I said with an eye scrunch. “You could easily return it, explain the mistake—you could just talk to the guy you talked to before. But, on the other hand, you got away with stealing a hundred-twenty buck watch.” Indignant starts on both sides. “Go return the thing.” I scooped it up and tossed it at Grant, who barely caught it in his distaste.

Spizzo’s brow cleared and he sprang up. “Okay. You got wheels, Merce?”

“I don’t think I’m getting involved in this further.” I saluted them and looked around for a better source of procrastination.

“You’re kidding. You can’t leave me with him; he’ll just end up making me pay for the thing! Come on…Mercy…” Grant’s pleading face stopped just short of doggish. Spizzo grinned-- a real one this time, no heartbreaker for us—and grabbed my bag.

“He’s probably right, plus now I have your keys.”

I looked down at my French, blurring my eyes so the words hurt. “Standard, huh. Did they have books on sale?”

Grant matched Spizzo’s grin as the smell of victory met his nostrils. “All the trashy nineteenth century novels you could want.”

“Even some reputable ones,” Spizzo added from halfway out the door. I watched the waitress, cleaning the shining tables, pick up her head and watch him down the street, and then suddenly she caught my watching and smiled sadly. Grant had already grabbed the papers covered in the French subjunctive and was gone too. Somehow I couldn’t turn to look at her again, as I stepped into the sun and bustle, swinging my hair and laughing at Spizzo, who was my friend and always would be. Lucky me but how bittersweet, all that gorgeous boy right there, and I know him so well, far too well to know that it will never happen.

They piled into my car, my navy bus, Grant in front because his iPod is the best by consensus. It’s only five minutes to the Standard on foot, but my yacht draws traffic like the evacuation of New Orleans.

Stopped at a red I look at Grant, laughing at Spizzo, so brightly lit from the sunlight off the hood; Spizzo in the back, laughing at me, hanging off the headrest of Grant’s seat. Our swept hair marks us cared for, but our dark glasses mark us rebels.

Maybe at some point the Standard was like other stores, handily advertising a vein of interest and then catering to it, but no longer. Now it caters to us, a mess of wares in all degrees of use and taste. The building itself sprawls over a whole block, a grey stone front carved in whorls and lines. Through the preposterous double doors, the kind with a bronze bar in the middle, the lobby has a sunk-in, cavernous feel. The whole place is just amazing. It takes a whole day to look through one wing. The sidewalk sales are famous: reclusive backroom items brought out to face the sun. Pressed to the walls are shelves of paperbacks, jewels in tattered covers.

Spizzo and Grant sent up a collective “Ehh!” as I maneuvered clumsily into a space.

“What happened??” I jerked my head around, peering at the swirling crowd.

“That’s the guy we talked to. Come on, Grant, this’ll take her ten minutes.” Spizzo jumped onto the sidewalk, planting both feet and standing to his full height. Grant scrambled to follow him, pulling his iPod cord behind him like a leash. Sighing, I turned back to my task.

By the time I arrived on the scene they had cornered him. He looked nice enough, well-meaning in a careless sort of way and he took the price tag with surprise, looking up into Spizzo’s face.

“Good of you to return this, boys. When I was your age, it would have been a pretty nice deal,” he said, draping the watch over a tin lunchbox. Grant grimaced at me across his back. God, I was tired, tired of the whole stupid thing, and wanted to go home, back to Dad and college pamphlets and Kylie flitting in for free food punctually at six. The boys had started browsing again, an endless loop of weekend monotony, tame emergencies and wistful hours.

I clapped them on the back. “Bring me something worthy of my talents next time, okay? I’ll see you tomorrow.” Always leave with a bang, if you can. It’s probably because she’s leaving but I’m realizing how much I’d soaked up from Kylie. It feels like nostalgia.

I skipped away grinning at them before they could argue, all in the spirit of my grand exit, and took the long way home. Too late, I realized I hadn’t eaten any pizza, indeed anything all day, and I squeaked into a Wendy’s drive-through.

The street lights illuminated the emptiness of the parking lot and the fullness of the line, and even though I was torn between staying out and heading home, lines are instinctually to be avoided. So I swept my bus to the left, barely cleared the bushes, and bumped a wheel over the curb into the parking lot.

She came out of nowhere. Again the cliché, but literally she seemed to appear from the light. Of course, she hadn’t, but afterwards when my hands were shaking and I was looking at them in that light, I couldn’t stop thinking, what was she doing there?

I was fine, except for the squealing brakes in my head. The yacht had seen to both. We—my car and I—were surrounded by a crowd of Wendy-goers, half pressing to see and half holding them back.

She sat huddled in her mother’s car, a blanket hiding her bruises, while her mother screamed abuse at the hood of the yacht. The police lights had receded into the distance already. I had submitted to a Breathalyzer administered by the most bored cop I had ever seen and gotten back into my yacht-shaped security blanket. The drive-through line evaporated and I pulled backwards into the street, driving like a spy in a movie—paranoid and fast.

At home Dad and Kylie were having a powwow in the doorway. I pushed through them (“Have Mercy!”) and slammed the door. I should probably start keeping a cliché diary.

I could have hurt her. I did. I did.

Hell, I could have killed her. She could be dead right now. I would be responsible, utterly and completely. I wouldn’t even have been drunk. Just stupid. Just young.

After twenty minutes of reliving that half second I dragged myself up from the floor. Facebook wouldn’t work as a distraction. Sporcle certainly didn’t. I called Spizzo, knowing Grant would still be with him.

“Merce! How goes it?” Spizzo’s voice was backlit by the buzzing laughter of Grant’s freshman sister Josey. My heart eased a little and then tightened again. Of course I could tell him, sob out the whole short story and then demand to talk to Grant, give up on both of them and talk to a girl, who would be adept at care. Emotional involvement ahead, hard to starboard!

“Hey,” my own voice felt thick in my throat, alien. “Grant still has my homework.”

The phone changed hands, exposing me to the blasting music of wherever they were. Grant must be so bored. “Yeah, actually I can bring it over right now. You’re home, right?” So bored he was willing to come to my house? He would want entertaining, or he would follow Kylie around asking her about colleges. No, no, no.

“Not tonight, Grant, give it to me tomorrow. Say hi to Josey for me. Bye.” Brusqueness for the win.

At nine I realized that yet again I had failed to eat. Mom was in the kitchen cleaning the counters obsessively. I braced myself in the doorway, seeing the waitress Spizzo had liked and left, then seeing her I had almost killed.

“Sweetie, there’s pasta, and I think some meatloaf. Oh, actually Kylie ate the meatloaf. I tried to save it for you,” Mom said brightly, swooping down to kiss me.

Thanks, Mom, I appreciate it. Notice my despair? “Pasta’s fine.” The tomato sauce had clumped to the noodles in a cold, unappetizing way, and when I opened the microwave the ceiling was peppered with red grease.

I moved through the house in a trance, settling into the corner of the sofa downstairs. Through the glass of the door, our neighbors’ pool was that strange pool-moonlight, lit from below. The Tupperware empty, I lifted my hands again to block that Godforsaken light. The tremors started in my elbows now, winding up my forearms to my palms, twitching my fingers.

Sleep and wariness alternated all night. I have never been as exhausted as during that night, laying on the couch praying for sleep.

At six thirty, my phone, lodged in my pocket, sounded another triumphant sunrise. I hauled my carcass into the shower before my parents could discover me passed out downstairs. Despite being home early and seeing Mom at nine, assumptions would be made.

School on probably three hours of sleep is manageable if you play it right, but school with no sleep and shaking hands? Thrown to the lions. n.o.m.e.r.c.y.

I opted for simple, cringing from attention. What if somebody had seen, and approached me? And again I saw it, felt my bus hop over the curb, saw her, felt the resistance of the brakes, the slightest, slightest impact.

For the first time I wondered who she was. I set my head on my chest-of-drawers and let my selfishness overwhelm me. How tall had she been? Could she have been my age?

Do I know her? Somebody knows her, Mercy. It’s not all about you. In fact, this is all about her. You are actually the bad guy this time.

Freshmen year I discovered a phenomenon called Butterfly Days. If you feel disconnected from everyone and all you’re doing is alighting on each class, sucking out the necessary information, and leaving with your chin up, you’re experiencing a Butterfly Day. Butterfly Days are supposed to run smoothly with minimal interaction or problems, to give you time to think and feel better. Today, naturally, I got no cooperation.

AP bio sprung a quiz that was less pop than bang. Kevin Mueller wouldn’t leave Nina Detih alone during the lecture afterwards, the pervert, and so I was switched with him. Nina’s ok but she’s stupid, and stupid people tend to be needy during lectures. So first period did not leave me in a good mood, or a Butterfly one.

Grant was waiting at my locker when I schlepped over there. Ah, yes, the French I hadn’t done. Whatever, I knew the subjunctive.

“Thanks buddy,” I said through my teeth as I wrestled with my locker door. Grant stooped down and popped it open. “Yeah, definitely thanks.”

“You okay?” He asked suddenly, examining my face.

“Wha—“

“I know it’s been hard, Kylie not being around a lot. I know if Josey was like that I’d be freaking out. ”

“Oh. Yeah, fine. She’s her own person, and I see her enough. Can always call her and stuff,” I said off the top of my head, totally nonplussed. Grant’s my best friend and he can’t even pick out the real cause of my not-okay.

He walked me to French, going to regular sophomore Latin next door. There’s a picture of Paris in the morning, in spring, tacked over the whiteboard in my French classroom. That’s what keeps me going. I’ve even picked out which garret I want.

Madame LeBouche, however, did not inspire a love of French anymore than a caricature of it. She spoke with this tremendous accent, even in French, wore enormous amounts of sleek, heady perfume, and her name! There was a school bet that she was really called Leonard or something and had it changed for the atmosphere. Though how being called Mme. the Mouth added to the atmosphere was beyond me; it wasn’t even witty. Her teaching had flair but no drive, and if you didn’t perform it was a rough class.

I had pretty well given up on my Butterfly Day when I settled in for the test review and a good thing too, for the LeBouche was in fine form. Ed St. Jones had transferred in from freshmen Spanish last week due to conflicts with sixth period basketball and he was having a predictably hard time. Every time he was asked a question, and she chose him every third question, he stumbled and she swooped, wings tucked.

“Uhhh…quiero que usted estudie. Sorry, wrong class, I know, I’m trying to connect them…” Ed’s voice tapered off as he was hit by a wall of scent, the LeBouche leaning towards him. She stalked down the aisles, swirling her perfume around us and demanding French verbs.

How have I put up with this class? Why? Paris. This is really happening, depend on it.

The bell rang and I jumped over Ed St. Jones’ foot in my haste to escape. The halls were filled with clumps of people, the muted blue tones of the walls outlining hair and hands and eyes. The flow pulled Grant and I towards lunch and Spizzo. Again I felt light, transcendent. My eyes slid over faces and lockers, searching for knowledge, for judgment.

The cafeteria, thank God, was a large, airy space—a converted theater. Grant opened the door for me and smiled off the side of his face. It caught what I had been saying and threw it away. What?

“Have you ever felt like you didn’t quite know where you are? Like in a familiar place, something unfamiliar happens and you’re jarred from it?” I asked him slowly, hitching my bag higher onto my shoulder to cover my confusion and covering my face with my hair.

“Yes.” His terseness was so sudden that I looked straight at him, the set lines of his face, and followed his eyes across the room.

The skylight poured fractured-sunlight onto the table where Spizzo and Josey twined around each other, eyes shut to the world. I think I clutched at Grant’s arm, but I’m not sure, because I stumbled into the hallway and slid down a locker without taking a second look. Grant followed me, not wordlessly, though my dazed face might have been a clue to shut the hell up.

Well, Mercy, you knew this would happen. You knew Spizz was a player (cliché? Check!), you knew he was into Josey, you knew Josey was smart enough to get him and dumb enough to be blind to the inevitable conflict with Grant. Forget it. I’m leaving.

“I’ll maybe see you tomorrow, Grant. Probably,” I tossed at him over my shoulder as I jogged towards the parking lot. Running is a big theme these last few days. Hit-and-run? Almost.

Safe in my car I listen to the silence and see the lights, bright, white, blue, burst. Where is there no light? I crack my eyes open and bring the car to life, inching out of the parking lot like a ditcher with a mission.

The Standard, a testament to its sundry talents, is currently attracting an elderly demographic to the sidewalk sale. That means carpools, which spells heaven for the parking-impaired. I take up easily two spots and move purposefully away, dispelling suspicious looks by focusing. The lobby unfortunately does have light to illuminate its carved-out space, and while I’m checking my bag at the desk I’m forcibly reminded of the cafeteria.

The book wing, however, smells like leather and salt, a testimony to the age of these tomes. The rooms’ moisture and heat are closely monitored, blinking steadily on each door on new and shiny panels, the only new things in the whole space.

I wandered down the stacks just touching the spines of the books of either side, both arms outstretched in a plea. The leather of each book to the next slipped from my fingertips, the slightest, slightest impact. When my arms began to shake I dropped them slowly, feeling it. I stood with my head tilted up at the sky through the arching wood. I know you’re there, Sky. Please. Light. And the lamps blurred to light as my tears filled the wells of my eyes, as if from rain after a long drought, washing through the country of my face.

I think half an hour later another patron found me, a woman of the geriatric persuasion. I actually really love older people; they have worldliness-- even if they’ve never been anywhere they’ve seen bad things change. She smiled gently and, without saying anything, thank God, took me to the bathroom and then let me fix myself. I was almost in tears again, I was so grateful.

She brought me outside again, retrieving my bag herself and installing me squarely in an armchair at the sidewalk sale. She smiled again and patted my hand and said:

“Don’t you cry anymore today, sweetie. Cryin’s for any day but Monday.” Is that a real thing and I just never heard of it? Or did she totally make that up? Whatever, it worked.

I wondered as she walked back inside who she was, who her grandchildren were, her husband. Did she know her? I blinked twice and got up from deep within the armchair, pulling my butt behind me. The sidewalk sale was winding down; the items beginning to disappear back into the infamous back room. A doll, made of snow white china and bloody velvet, looked at me pleadingly, while her companion, with glossy jet curls, gazed sternly over her starched collar. Next to them was a Speed Racer lunchbox, with the whole cast on it. I picked it up, grinning at the little monkey, and something small fell on my foot. I crouched to pick up the watch that Spizzo and Grant had had such trouble with—Spizzo, for whom I had fixed this easy problem. I sighed, placing it back in the lunchbox. Did it really merit one hundred and twenty bucks? I looked again at the matte black watch, the neon face, the…lack of a price tag. Once again it had fluttered to the ground. Jesus, this was like a habit.

“Excuse me, this watch—“ I proclaimed, marching up to the salesperson.

“Again? It happened yesterday too. Oh, you know, you returned it with those boys.” The same guy was on duty, the same careless guy who obviously hadn’t taken care of the problem, who said he would have taken it if he was us. “Thanks so much for bringing my attention to it again. I’m really impressed by the conscientiousness you’ve shown here.” The same guy who approved of conscientiousness and could use the word?

“Uhhh, thanks very much. You try, you know.” I was kind of touched, actually.

“You know what,” he leaned towards me slightly, wanting my name. “You know what, Mercy, that watch has been sitting out here for a year now because it doesn’t have a battery, but all anybody knew was that it didn’t run.” His mouth twitched. “Do you want it?”

“Ummmm, yes. Yes I do.”

He winked. “Batteries are at Rite Aid for three dollars.”

And then he walked away to another customer, and I held the watch in my hand.

What did I want in my life? How would I conduct myself to get it? It changes so fast, you know, what teenagers want. That’s why we cry. That’s why I cry-- I’m giving up pretensions for Lent.

I want to be like him, flexible on the front lines to help a girl in need, an apparently deserving girl. I want to be like my elderly friend, quiet and safe and able to judge what’s right. I want to be like that mother, defending her daughter from danger even afterwards. I don’t know about Kylie—about Kylie my heart breaks. And Spizzo and Grant can wait for me. I deserve it.

I laughed into the sky and drove home.

Similar Articles

JOIN THE DISCUSSION

This article has 0 comments.