All Nonfiction

- Bullying

- Books

- Academic

- Author Interviews

- Celebrity interviews

- College Articles

- College Essays

- Educator of the Year

- Heroes

- Interviews

- Memoir

- Personal Experience

- Sports

- Travel & Culture

All Opinions

- Bullying

- Current Events / Politics

- Discrimination

- Drugs / Alcohol / Smoking

- Entertainment / Celebrities

- Environment

- Love / Relationships

- Movies / Music / TV

- Pop Culture / Trends

- School / College

- Social Issues / Civics

- Spirituality / Religion

- Sports / Hobbies

All Hot Topics

- Bullying

- Community Service

- Environment

- Health

- Letters to the Editor

- Pride & Prejudice

- What Matters

- Back

Summer Guide

- Program Links

- Program Reviews

- Back

College Guide

- College Links

- College Reviews

- College Essays

- College Articles

- Back

Plighted Troth

June in Ireland meant the sun was up for over fifteen hours, the trees in the parks were green and full of life and people crowded the street like flurries of ants, swarming through the narrow cobbled passages in their daily hurry. I was staying with my mom at The Merrion, an old-fashioned family run hotel in the heart of Dublin. As dusk approached, I was starting to get hungry, so my mom and I decided to look for a restaurant. We picked up our shopping and began heading down a narrow, winding street, towards a famous pub reputed to have the best boxty, the traditional Irish potato pancake, and local red ale. On the way, the coruscation from a jewelry shop caught my eye. It was filled with ornately carved Irish rings, hand twisted bracelets and braided necklaces. Gold Celtic pins and pendants spangled the window-frame, glittering in the fading sunlight. My mom relented, and my heart leapt to my throat as the tinkle of the bell announced our entrance, door swinging shut with a dull thud behind us.

Inside, the store was spooky. I felt uneasy as I walked past rows of heavy golden orbs and stained silver teapots. I ran my finger across the rough ridge of a serrated bejeweled blade, until I felt the angry gaze of the shopkeeper, an old, wrinkled man. I flinched.

“Welcome to my store,” he said. He did not sound inviting. “Are you looking for something special?”

I did not have the faintest clue what to say. Staring at the shopkeeper, tufts of fluff sprouting from large red ears, a bulbous nose and sparkling gray-green eyes, I felt mystified.

“Just looking,” mom to the rescue.

“Heading anywhere special?” He asked.

I thought, What an odd question. “Um,” I said. He shot me an exasperated look, making me cringe further. “We’re going to Wexford.” I managed to stutter. Why did he make me so tense?

“Good!” He guffawed, slapping the glass counter-top with a gnarled, bony hand.

“You will want to look at these,” he added, pointing to a set of rings. “They are Cladaugh rings, you like? Ho-ho-ho…”

I cautiously approached him and took a peek. Sure enough, the rings were gorgeous. I was captivated by one in particular. It had a smooth heart at the center, held in place by two strong arms, with a crown fanning out of the top.

“Yes,” I breathed, reaching my hand out.

“Ho-ho-ho,” He said, “I knew it! Very special, that one!”

“Ah, good choice. Good choice.” The man pulled out the ring. “This is a Claddagh ring.” He said, slipping it on the index finger of my left hand. It fit perfectly and felt oddly warm to the touch.

“Claddagh,” I said, liking the way the word bubbled from my lips.

The ancient shopkeeper nodded, face stretching into a smile. “This one is an antique,” he said, “traditionally used as wedding rings or rings of love and courting.” The ring was just 40 euro and bought my mom peace through the six-hour car journey ahead of us. We bid farewell to the shopkeeper, door thudding behind us.

The drive up to County Wexford was largely uneventful. In fact, though the view of lush green pastures, sweeping mountains and cows grazing was beautiful, I spent most of the ride curled in a ball, fast asleep.

While I slept, I dreamt. I saw a handkerchief with loopy initials, and pale ghost of a hand slip a glittering golden object into it. I saw two hands touching each other. I smelled smoke. Flames. A vivid crimson.

I rubbed my eyes, jolting awake. My eyelids danced in pain as the sun had been shining directly on my face. The car shuddered to a halt as we arrived at the farm.

We were met immediately by Kit, one of the heads of the program. She showed us inside the main farmhouse. Two dogs, Al and Dozer greeted us, tails wagging playfully, noses on the floor, sniffing. We were served piping hot coffee diluted with cool milk and dense Irish wedding cake from the past weekend.

After tea, mom said her goodbyes, leaving me to my own devices. Kit and her husband Bob were busy preparing for the rest of the group to come the next day, so I had the rest of the afternoon to explore the lay of the farm by myself. I set out with Al, a shiny shorthaired chocolate lab, over a low-swinging metal gate through a stretch of shaggy grass. My calves were stinging as Al bounded in front of me, leading the way. I ran after him, clutching at the stitch that seared through my left side.

We ran to the edge of a great lake, bounded by delicate, white water-crowfoot flowers floating on the surface. We spent the day there. Al would fetch large rocks and bring them to me, waiting expectantly for me to throw them back into the pond. He would then happily leap into the cold, black water and re-emerge with a different rock, stick and once a soggy, algae-covered tennis ball, that was again promptly lost. As the sun began to fade behind the horizon, I watched the tall Elms sparkle, backlit and felt a chill creep into the air. I thought it was time to head back, but Al was gone. I heard the clicking of his nails and watched a dark four-legged figure disappearing into the forest clearing.

“Al!” He had no reason to heed my call, but I felt obliged to bring him back with me. I followed his approximate path and was folded into the prickly embrace of pines, elms and yews. I did not know where Al had gone, but I could hear his barks ahead of me. I pushed past a few low-hanging branches and found myself in a small clearing underneath a large willow. Al was there, tongue sagging, eyes sparkling, tail wagging. Then he was bounding onto me, his large, wet paws on my stomach. He knocked me to the ground and began licking my left hand. I pushed his face away, thankful for my prior experience with big dogs, and grabbed onto his collar. Together, we headed back to the main house.

Kit showed me where she kept the black tea, the milk, the sugar and we sipped our steamy mugs, eating the rest of the wedding cake. Bob was already at the airport, waiting for the rest of the kids to arrive. After washing the mugs in the kitchen sink and laying them on the white plastic drying rack, Kit lead me upstairs to my room. There were three bunk beds and a row of white cabinets pressed against the right wall. I chose the bed to the far right, closest to the windowsill, and put my things into one of the cabinets, making it mine. The boys’ room was adjacent to ours, but their beds were oddly close together. Sitting on the lower bunk, I often bumped my head against the scratchy wood. Kit left me alone to get some rest and I fell asleep to the deep country silence.

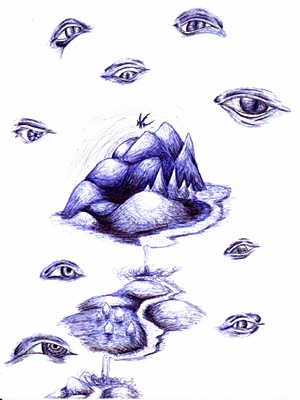

That night I had another vivid dream. Trees from the clearing, chanting. I see a woman, the same woman that I dreamt about in the car. Her pale face is framed by scarlet hair, and her bright blue eyes are accentuated by a fan of red lashes. A man. Bright eyes and dark black hair. They hold hands and she kisses him lightly on the lips. Then the flickering of flames, again, following screams and chanting. What are they saying? I look around and am surrounded by trees, elm, yew, oak. I cannot breathe. I feel choked and gagged. I struggle for air… It felt so real that I woke up disoriented, staring around the room in confusion. My breathing was coming on irregularly and heavily, as if I had been gagged and bound. My arms were shaking. I spent the rest of the morning reading The Dubliners in bed, trying to push the dream away from my consciousness.

The first week was filled with name games and contour drawings. Kit was our drawing teacher and every morning we would walk along the lake, pick a spot, and draw all we could see. I learned to sketch quickly and stop caring about silly mistakes like blurry edges or stray lines. We used graphite pencils. HB was the lightest and most brittle, then 2B, 4B, 6B for the deeper, richer tones. Kat always grumbled about our morning routine. She had come mostly for the photography and disliked drawing immensely.

Nights in the darkroom filled me with first awe then creeping boredom. I learned to love film photography only after whole rolls of blank, overexposed film, struggling with the aperture, lens and zoom. Bob demonstrated each step of the developing process, losing his patience when May spilled the chemical developer all over the floor and cursing loudly when Sean cut himself trying to open the film canister in the dark. Roo, Paul and Kat all loved photography, and the hours between 10pm and 3 or 4 in the morning were all theirs.

I was loitering in the darkroom after drawing lessons during the second week of my stay. Kit had introduced our first painting project – acrylics on 3x5 feet sheets of paper of trees. There were a few places I needed to explore before I began my painting, but it was raining, so I thumbed through the dry prints, instead. I stopped at a picture of Kat. She was crouched in a clearing of trees, but there was a strange smudge next to her that I couldn’t quite make out. I brought the photograph into the studio to study it in brighter light. It was then that I realized where Kat was. I had been in that same clearing on my first day at the farm. I went back inside the darkroom and replaced the photo of Kat before sprinting back to the main farmhouse. I ran up the stairs, pausing to wave to Bob through the kitchen’s double doors. He waved back at me, his hands slightly bloody from the meatballs he was molding. I found my pale yellow raincoat and slipped it on, pulling on coarse red woolen socks before dashing back down the stairs. Sarah and Kat waved absentmindedly from behind their computer screens.

Outside I pulled on my wellies and was soon joined again by Al.

“We meet again,” I murmured, scratching him behind the ears. He squirmed out of my reach and began trotting down the same path we had taken that first day. Following closely behind, I paid careful attention this time to the route we were taking, making a mental note of the left turn after the hammock and the right turn after the large gnarled oak.

As we headed into the denser part of the forest I turned to look at the lake, and watched its pristine surface shatter from the constant flow of raindrops. My hands were cold but my cheeks were flushed and warm. When I turned back to the forest I watched Al ahead of me, disappearing through the thicket of trees. I followed, breath catching, and sprinted blindly ahead.

When we made it to the clearing, it was already occupied.

“Hey,” I walked up to Etta, a girl with deep auburn hair. She was crouched by the roots of a large tree.

“Etta?” I walked over to her and tapped her on the shoulder. She nodded her head once before resuming her stance. Her eyes were wide but unseeing. It unnerved me. Her hair was damp and I realized she was barefoot, without a raincoat, and spattered with mud and grass.

Suddenly Al was bounding back towards us and barking very loudly. The sun seemed to be getting dimmer and I was starting to panic when Etta finally turned to face me. She looked scared.

I looked at her and felt an immense comfort when she met my gaze. And then I was screaming and hugging her and we were walking back towards the farm, following Al, still barking madly at nothing. The rain was beginning to dither, coming down in little sprays of cold mist, but we were both shivering by the time we got back to a table of hot pasta, cool milk and worried adults.

The expression on Bob’s face begged an explanation, so we told our story in between bites of spaghetti and meatballs. Etta began with this morning, when our painting project was first introduced.

“I had seen this clearing of trees and new immediately that I wanted to paint them. It was a weird feeling I got, I just had to be there.” She said, fork scraping the white china. “Well it started to rain, and I thought I’d just wait it out in the clearing. I was mostly protected by the canopy and it wasn’t too cold. Then I remember seeing Ani and being very, very cold, wet and somehow it was hours later.

I nodded, continuing. “I had gone to the same clearing on the first day, with Al. Then today I was looking at a picture of Kat and she was in the clearing.”

I managed to finish my story with minor interruptions from Kat, Sean, and yowls from the dogs outside. Everyone listened but talk soon returned to sports and movies and Etta and I exchanged an exasperated glance.

After dinner, our questions were answered.

“Girls! Come down!” He sounded stern. “We’ve got a bit of talking to do.”

“I’ll fetch you two some hot tea.” Said Kit.

Bob’s voice came out a low growl. “There was a family by the name of Kerry. Lived in a large estate up the hill. They owned some of the property that is now in Kit’s family. Their land ended it that clearing you two were in.”

“They were a rich family and during the famine, many felt cheated and angered by their wealth. One night an angry mob congregated in town and the Kerry family had not a chance. They were all killed: chained together, burnt, dead on the tree.”

I gripped Etta’s hand. It was sweating.

“Legend has it that the young Mr. Kerry had a lover. She was a poor town girl, but she was born from an old aristocratic family that had lost their money due to alcoholism. She and Mr. Kerry were said to be betrothed.” I felt Bob’s stern gaze on my left hand and cringed backwards.

“She died shortly after. It is said that she died of a broken heart.”

Kit reemerged from the kitchen, carrying two steaming mugs of milky tea. She was grinning though I felt sick.

“Don’t let Bob scare you,” she put the mugs on the table. “It’s only an old story.”

I glanced over at Etta, who looked as fearful as I felt.

The next week passed without mention of Kerry’s Trees. The other kids didn’t believe in it but I was beginning to feel a coldness from Etta. Each night the dreams continued. They were more fluid now, less broken-up.

The woman beckoning, the man following. Passionate embraces followed by hot stares and little smiles. The young woman is often beaten by a grizzle, florid faced man. Her father, presumably, a raging drunkard. Her mother, meek, mild-mannered, shies away from it all. She hides her love from them. Her lover, Mr. Kerry, caressing a gold ring. A gold ring. The ring. I can barely make out the hands grasping at a heart. Then the flames. The flames and chanting always come. I feel the hatred searing through my organs, guiding me into the waking world.

That Saturday, I somehow found myself back by the clearing, caught in a heavy thunderstorm, and took shelter under the largest tree. To my surprise, Etta was already there. She was sitting crouched by the twisting roots, her eyebrows knit together in concentration.

“Why are you here?” She hissed, rocking forward on her feet.

“You shouldn’t be here, it isn’t safe.” She was staring distinctly at a specific point in the tree, but I could not make out what caught her interest.

“Do you really believe that stuff Bob said?”

“He was just being an a**hole.”

“But what about what Kit said? And what did she mean?”

“Dunno,” Etta said, facing me finally. Her eyes looked sullen and dull. I cringed away, planting my palms firmly in the damp soil.

“Do you ever get feelings about a place?” Etta asked. Her blue eyes bore into me with a tentative force. I nodded.

“Like, stepping into an old house,” I said, “and sometimes, I just feel weird. Like something bad happened.”

“Like something bad is always happening.”

Memories. I recalled a passage from an old book of legends I had read a few years back. It went into detail on memories and imprint hauntings. How past conflict and pain can literally remain in a place long after the initial act happens. I filled Etta in and we both decided to meet in the loft above the darkroom at dawn. We ran back to the main barn, arms over our heads, sprinting fast and breathing hard. Lightning flashed above us, and my thighs burned from the exertion.

We ate dinner in silence. I let the chatter and noisy bustle from the rest of the group engulf me as I focused on each bite of food. I was floating, reeling back to the trees, the rain, and Al’s barking. Smoke everywhere; the trees lit by flickering licks of fire; a mob, and muffled screams. I look back at the tree, teetering as acid bile rises up my throat. The Kerry family, gagged and bound, tied to the tree. The mob, surrounding them. Starving people. I am crying, hands pressed over my face. I removes the ring, wrapping it in a handkerchief. I place the bundle in my apron pocket. Several urchins hang back, spotting the glimmer of gold. They jump at me. I scream. They tear at my clothing with dirty browned hands. I run.

Then I was back at dinner, smiling weakly at Sean, his eyebrow raised into quizzical concern. I let myself zone out as the conversation flowed gracefully to politics, current movies, bands, and sailed through the next few hours, nodding and smiling on cue.

Nightfall eased me out of the farm and then I was briskly walking towards the clearing, lungs expanding with fresh Irish air. Etta was there when I arrived, sitting on a large, smooth rock. Legs crossed, eyes closed, she looked calm and peaceful, like a Buddha.

“I’ve been meaning to ask you,” I said.

“Yeah?”

Our footfalls were making a clomp-clomp noise in the dense, muddy grass. I took a breath and began, “look at my ring.”

Etta examined it and frowned. “Can I see it closer? Try it on?”

“I’m afraid not.”

“Why?”

“It won’t come off.”

“It does look a bit tight,” she said.

“No, that’s not it.” I said, “touch it.”

She put a finger to the gold band and quickly pulled it away. “That is hot!” She said, reeling. I nodded but said nothing.

“Isn’t it, that ring, I mean – “ Etta’s gaze was fixed on the heart in its center.

“It’s a Claddaugh ring,” I said.

“Bob kept staring at it, while he was telling us that story.”

“I know.”

We walked a few more paces in silence.

When we passed by the lake, a ripple in the water made me pause. It was only Al, though, diving for rocks again. He bounded out of the lake, fur misting cool drops of water around us.

“Hey, hey, Al!” Etta said, pushing him away with a hand. “Off, boy.”

“He’s only saying hi,” I said. I scratched him behind the ear. He lurched away from my touch and then his massive body was slamming me from the side and I stumbled into the shallows of the lake.

It is raining and my skirts feel heavy and water-logged. I am shaking. My hands are so pale. Running legs desperate to escape. I struggle for a breath but instead, silence envelopes me. I watch the handkerchief floating away from my body and the ring falling to the lake bottom. Peace.

“Ani!” A dull throbbing sensation pulsed at the back of my head. I could hear shrieks but did not know where they were coming from.

“Ani,” Etta said, again, “you ok?”

“Etta, I think I know what happened now,” I said. I recounted my visions of the woman and the lake. Etta, in turn, nodded, shrieked and paced.

“What now?” She asked.

Just then I felt a pulse of heat on my index finger and felt the ring loosen almost instantaneously. I slipped it off, examining it.

“I am certain this was her ring,” I said. “I think she wants it back.”

With that, I clasped the ring in both hands, and, eyes closed, tossed it back into the depths of the lake.

“I hope you find peace,” I muttered.

“I think you did the right thing,” Etta said, slipping an arm over my shoulder. We walked together, shivering slightly. Hot chocolate and sweet tea was waiting back at the farm.

That night I dreamed of the two lovers, entwined in each others arms. A pale arm entwined in another’s. A long embrace. And the Claddagh ring, at the bottom of a lake, an eternal unity.

Similar Articles

JOIN THE DISCUSSION

This article has 0 comments.