All Nonfiction

- Bullying

- Books

- Academic

- Author Interviews

- Celebrity interviews

- College Articles

- College Essays

- Educator of the Year

- Heroes

- Interviews

- Memoir

- Personal Experience

- Sports

- Travel & Culture

All Opinions

- Bullying

- Current Events / Politics

- Discrimination

- Drugs / Alcohol / Smoking

- Entertainment / Celebrities

- Environment

- Love / Relationships

- Movies / Music / TV

- Pop Culture / Trends

- School / College

- Social Issues / Civics

- Spirituality / Religion

- Sports / Hobbies

All Hot Topics

- Bullying

- Community Service

- Environment

- Health

- Letters to the Editor

- Pride & Prejudice

- What Matters

- Back

Summer Guide

- Program Links

- Program Reviews

- Back

College Guide

- College Links

- College Reviews

- College Essays

- College Articles

- Back

The True Impact of C.T.E.

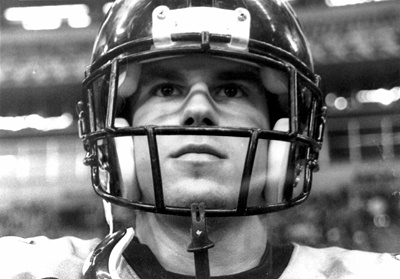

Owen Thomas, a 6 foot, 240 pound lineman started playing football when he was nine. Throughout his years at both middle school and high school levels, he had never suffered a concussion, but was known for being tough and hitting hard. Owen’s hard work and talent led to him being offered an athletic scholarship at the University of Pennsylvania to play football - an offer he gladly accepted. Owen excelled there, earning the title of second-team all-league lineman in 2009. In the spring of Owen’s senior year, however, things began to deteriorate. He voiced to his family that he was feeling stressed about school, worrying that he was going to fail at least two of his classes. On April 26, 2010, he was found dead in his off-campus residence; he had hanged himself (Penn Football Player, 2010, September, 14).

This event was forgotten within weeks at the school - a classic case of not being able to handle the stress of an Ivy League school. However, almost a whole year later, researchers at Boston University offered an alternate explanation for Thomas’ sudden and uncharacteristic death. When Ann McKee, a neurology professor at BU, examined Thomas’ brain, she noticed telltale signs of Chronic Traumatic Encephalopathy (CTE), a disease found in many deceased NFL players. The symptoms of the disease can include confusion, memory loss, a drop in concentration, and, most notably, depression (MedicineNet - n.d). In the case of Owen Thomas, as well as other victims of CTE, the depression can lead to suicide.

Owen Thomas’ story, while a sad one, is not an unparalleled one. In the last ten years alone, there have been an alarming number of suicides by football players. In a small study, eight popular players who ended their own lives were examined post-mortem and were all found to have CTE (Former football players' suicides tied to concussions. n.d.). Terry Long, the offensive lineman for the Pittsburgh Steelers was found dead in 2005 after drinking antifreeze. CTE was determined to exist in his brain. Andre Waters, a safety in the NFL for both the Steelers and Cardinals shot himself in the head the year after. CTE. Jovan Belcher, a 25-year-old linebacker for the Kansas City Chiefs shot his girlfriend moments before taking his own life. CTE was present (Former Football Players, 2014, December 1). The list goes on and on, but the question remains: how many more lives have to be cut short before serious changes are made in the world of contact sports?

As football becomes an increasingly important aspect in American society, and athletes start their hopeful careers at earlier ages, the topic of mental health needs to expand by leaps and bounds to avoid an epidemic for football players. CTE is a very important disease that is exponentially more harmful than people think. Leaders in the sports world need to communicate the importance of the disease quickly and effectively to prevent a worse situation than already exists.

Scientists who have been involved in the research of CTE have outlined four major stages. The first stage is defined by headaches, mild loss of attention, and loss of concentration. It can also include depression, but only in rare cases. The second stage is much more severe. It is also marked by headaches, concentration problems, and memory loss, but added to the symptoms are mood swings, and the possibility of suicidal thoughts. When Owen Thomas’ brain was analyzed by Ann McKee, he was found to have Stage II CTE, not the worst stage, but bad enough for trauma-induced depression to set in. If Thomas went on to play professional football, the disease would have only gotten worse. Stage III entails, along with all of the previous symptoms, visuospatial issues, difficulty with decision making, and increased apathy. Stage IV, the worst stage, is marked by more serious memory loss, loss of concentration, aggressiveness, language difficulties, paranoia, and depression (CTE Center | Boston University - n.d.). The more impacts the brain receives, in other words, the worse the symptoms get.

From a neurological perspective, CTE is easy to spot. In the medical study, “Chronic Traumatic Encephalopathy in Athletes,” the authors note that “CTE is characterized by atrophy of the cerebral hemispheres, medial temporal lobe, thalamus, mammillary bodies, and brainstem, with ventricular dilatation and a fenestrated cavum septum pellucidum” (McKee, A., Cantu, R. 2010, Sep 24). Basically, the brain is a floating mass which is covered by a hard shell - the skull. When the skull gets bashed into repeatedly, the brain gets smashed around inside the skull, which results in nerve damage (The New Yorker. n.d.). The more smashes the skull receives, the more damage to the brain occurs. The symptoms of CTE happen because the parts of the brain that get crushed due to impact alter the subject’s consciousness. For instance, if the frontal lobe of a football player gets particularly damaged, he could experience personality changes (one of the possible symptoms of CTE), because personality is primarily controlled by the front region of the brain. Unfortunately, CTE - as of today - can only be examined post-mortem. However, it can be estimated if an individual has it. If a person shows the signs of CTE and has a history of head trauma, it can be estimated that the individual has the disease, but it cannot be known for sure (UCLA Study, 2015, April 16). Even if one was diagnosed with CTE, there would be nothing they could do to treat it. The only way to completely prevent obtaining CTE is to not participate in activities that promote repetitive trauma to the brain.

On the bright side, there has been significant progress made in the past few years dealing with diagnosing CTE while the patient is still alive. A professor at UCLA, Jorge Barrio, says that he and his researchers at UCLA have found the fingerprint for CTE in the PET brain scan. He discovered that when compared with the Alzheimer's test group, participants who were suspected to have CTE had much more FDDNP (a chemical marker used to highlight parts of the brain) in the subcortical and amygdala sections of the brain, the amygdala being the part of the brain that deals with emotion, especially anger. People with Alzheimer's, on the other hand, showed higher levels of FDDNP in “areas of the cerebral cortex that control memory, thinking, attention and other cognitive abilities.” The study also went on to find that athletes who had had more concussions had higher FDDNP levels (UCLA Study, 2015, April 16). Although CTE can not be diagnosed with absolute certainty on some athletes with a serious history of head trauma, it can be very safe to infer.

At the University of Chicago, additional progress is being made. The university has invented a new brain scanner that helps highlight the severity of CTE in living people by having a radioactive tracer light up the tau protein, a protein that is released as a result of trauma, in the brain (Tackling Chronic Traumatic Encephalopathy, 2015, April 21). Another recent study found that when five retired football players had brain (PET) scans done on them, which were then compared to adults of similar age and body mass index, the FDDNP was higher in all subcortical regions (below the cortex in the brain) and in the amygdala. All of these areas produce tau - the protein the brain releases after severe damage (PET Scanning of Brain Tau, 2015, February 10). These findings are all quite new, and the research is still in its experimental stage, but they will hopefully shed light on the importance of head injuries in the future.

At the lab at Boston University, McKee, among other researchers, studied 85 brains from deceased subjects who had a history of, at minimum, mild traumatic impact. Of the 85 subjects in the study, 35 played football in a professional league (34 in the NFL, and one in the CFL), with only one of the subjects showing no signs of CTE. There were three subjects that had Stage I CTE, another three that had Stage II, nine subjects having Stage III, and seven that had Stage IV (Brain, 2012, December 3). The other eleven deceased football players had CTE combined with other life-alternating illnesses, among them: Alzheimer's disease, Lewy body disease, and Pick’s disease, a form of dementia characterized by the shrinking of the frontal lobes. As the study showed, 28 of the 35 former professional football players were living with Stage III or IV CTE, or CTE combined with another morbid illness.

With all of these recent studies, then, it would seem that CTE is a relatively new disease - one that has just been discovered. The truth, sadly, is very different. The negative effects of traumatic head injury have been known since the 1920’s. It was first noticed in boxing, when old-time boxers started to become groggy mentally, and have trouble speaking clearly. It was named Punch Drunk Syndrome for its resemblance in symptoms to drunk individuals. It was looked into further the next few decades, and was discovered that 17% of professional British boxers from the 1930’s to the 50’s had clinical evidence of CTE (C.T.E. in Boxing. n.d.). Despite the evidence, boxing continued to be a prevalent sport, even increasing in popularity. A significant percentage of its participants receiving debilitating injuries didn’t deter the public from wanting to watch two athletes hit each other in the head repeatedly. Today, as the majority of the public is aware, boxing still exists. There are new safety implementations for modern boxing - the mouthguard, the ringside physician - but the basic premise is still the same: punch the opponent as hard as possible before he strikes first.

The problem is that all of those punches add up. In the same study done by Boston University, an alarming 7 of the 9 professional or amatuer boxers examined had Stage IV CTE (Boston University. n.d.), the stage where severe memory loss, depression, and paranoia set in. Even with all of the new safety measures taken by the World Boxing Organization, it is clear that many boxers still carry very serious mental issues with them until death.

American football has made many changes involving safety since its beginning, but like boxing, the precautions taken are nowhere near the magnitude needed to keep its players safe from CTE. In the 1930’s, some football players wore helmets to reduce injury while others did not. It wasn’t until 1941 that the NFL made helmets mandatory, and even then, the helmets were made of flimsy leather. In 1955, the plastic helmet with the single bar across the bottom was issued for all players in the league (The 1890’s: Brain Risks, 2015, July 28).

Since then, the helmet has improved dramatically, but even so, concussions have gone up. In 2014, there were 123 concussions in the league, while in 2015, there were 154 (Frontline: Concussion Watch. n.d.). Some explain this phenomena by claiming that the technology for helmets is too good, which leads the athletes to use their helmets as a weapon, unlike what they would do if there were no helmets (Football helmets are creating more problems than they solve, 2015, October 23.) It is obvious, however, that playing with no helmets would not be safer for the players. The fact of the matter is that what the NFL is doing right now is not working. Tweaking small rules like shortening the distance on a kickoff, or penalizing players for targeting the head are steps in the right direction, but relatively ineffective steps nonetheless. The National Football League needs to do something major and soon, to cut short the terrible crisis many families are seeing now - retired football players living with the disturbing neurological consequences from years of colliding with other athletes.

The NFL, it turns out, has a less-than-perfect record when it comes to keeping track of concussions. According to a book written by two writers for ESPN, The League of Denial: The NFL, Concussions and the Battle for Truth, “The National Football League conducted a two-decade campaign to deny a growing body of scientific research that showed a link between playing football and brain damage” (Don Von Natta Jr. 2013, October 2). The book went on to say “[a]s far back as 1999, the NFL's retirement board paid more than $2 million in disability payments to former players after concluding football gave them brain damage. But it would be nearly a decade before league executives would publicly acknowledge a link.” The NFL’s streak continued, say authors Mark Fainaru-Wada and Steve Fainaru. “Independent researchers directly warned Goodell about the connection between football and brain damage in 2007, but the commissioner waited nearly three years to acknowledge the link and to dismantle the league's discredited concussion committee. In 2009, two other independent researchers delivered still more evidence that football caused brain damage during a private meeting at the NFL's Park Avenue headquarters. Yet the league committee's co-chairman, Dr. Ira Casson, mocked and challenged the researchers so aggressively that he offended others who were present, including a Columbia University suicide expert and a U.S. Army colonel who directed the Defense and Veterans Brain Injury Center.”

Why did the NFL go through all that effort to cover up a few studies on concussions? Did they simply disagree with the research and want to get their point across? No. The real reason the NFL covered up all of the scientific studies was, quite simply, money. In 2013, the National Football League made over $9 billion in revenue, and according to the (multi-millionaire) commissioner, Roger Goodell, it could make up to $25 billion by 2027. The only way the NFL could ever lose money is if fans stopped watching the games on TV (or in person), or if the players themselves stopped participating in the sport because of the inherent dangers involved. Although both are unlikely, the NFL was scared of a loss of revenue and, as a result, covered up some very important evidence that connected professional football with serious head injuries.

To make matters worse, NFL doctor, Matt McCarthy, says that CTE is being “over-exaggerated”. He claims that there is still not a clear link between football and CTE (NFL Doctor, 2015, March 18). Not a clear link? Not enough evidence? Malcolm Gladwell, a best-selling author and writer for the New Yorker gave a speech at the University of Pennsylvania a few years after Owen Thomas’ suicide. In it, he told a story about coal miners, describing how a certain insurance executive found a huge link between working in coal mines and early death. The executive published his findings through the national bureau of health in 1918, but it wasn’t until 1975 before coal mining companies actually made any changes to the industry. When the study was published in 1918, the coal mining companies said that there wasn’t enough proof to link coal mining and health concerns. Gladwell articulated, “they were using the notion of proof as an excuse not to do anything”. Later in his speech, Malcolm switched the topic from coal mining to football. He likened the coal mining companies to the people in charge at the University of Pennsylvania after Thomas’ suicide - using lack of a proof as an excuse not to do anything (Malcolm Gladwell at University of Pennsylvania. 2013, February, 14).

Junior Seau was born in 1969 on the other side of the country, in San Diego. In high school, he played track, basketball, and football, lettering in all three. Junior then played football for USC, where in 1989 he was selected as an All-American for the linebacker position. He got drafted by the San Diego Chargers the next year, quickly becoming one of the most popular players in football. He moved on to the Miami Dolphins, and later to the New England Patriots in 2006. Over his lengthy career, he was selected for the Pro-Bowl a total of twelve times. In 2010, Seau was involved in a serious car crash when his car fell over a one-hundred foot cliff; luckily, he was alive, but in 2012, Seau admitted to his ex-girlfriend that the crash was an attempted suicide. On May 4, 2012, Junior Seau shot himself in the chest (Junior Seau’s Death, 2012, May 4.)

Later, when his brain was taken in for analysis, CTE was discovered. It turned out that Seau had been suffering with the consequences for years, struggling with insomnia for the last seven years of his life.

How many players are currently struggling with this disease? The number is unknown. What is known, however, is that many football players, as well as hockey players, wrestlers, and boxers have suffered cruel and devastating deaths solely because the corporations in charge of their well-being have ignored the mounting research on CTE and continue to do so. Something needs to be done.

Similar Articles

JOIN THE DISCUSSION

This article has 0 comments.