All Nonfiction

- Bullying

- Books

- Academic

- Author Interviews

- Celebrity interviews

- College Articles

- College Essays

- Educator of the Year

- Heroes

- Interviews

- Memoir

- Personal Experience

- Sports

- Travel & Culture

All Opinions

- Bullying

- Current Events / Politics

- Discrimination

- Drugs / Alcohol / Smoking

- Entertainment / Celebrities

- Environment

- Love / Relationships

- Movies / Music / TV

- Pop Culture / Trends

- School / College

- Social Issues / Civics

- Spirituality / Religion

- Sports / Hobbies

All Hot Topics

- Bullying

- Community Service

- Environment

- Health

- Letters to the Editor

- Pride & Prejudice

- What Matters

- Back

Summer Guide

- Program Links

- Program Reviews

- Back

College Guide

- College Links

- College Reviews

- College Essays

- College Articles

- Back

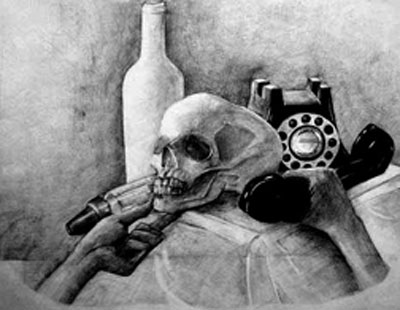

Up In Smoke: The Recondite Perils of Cigarette Smoking

It’s no secret that smoking cigarettes is a very unhealthy habit. Everyone knows that lighting up can land smokers with deadly lung cancers, heart disease, and chronic respiratory ills. However, while the most egregious hazards of smoking are for the most part widely-known, there are also many less obvious effects that together can combine to make a smoker’s life miserable long before cancer or cardiovascular afflictions take their oftentimes fatal toll.

As extreme as it may sound, the simple truth is that if something can go wrong in the body, cigarettes will either cause it to happen, or if the condition already exists, make it worse. Too frequently the media portray smoking as the causal agent of very localized ailments. For instance, a report might read: Recent Study Finds Cigarette Smoking Directly Linked to COPD. While such claims are invariably true, the problem arises in the wording which insinuates that COPD (or some other ailment) is an isolated problem. Such thinking is understandable, but inherently flawed. There is no such thing as an isolated event within the human body - everything, be it good or bad, causes a domino effect of sorts. For example, if one suffers a bone fracture, the natural assumption is that the skeletal system is the only thing affected by this unfortunate occurrence. In reality, however, many more factors come into play. What bone was broken? Was it a simple fracture and if not, in what ways did the shifting of the bone impact the surrounding musculature? Was there any potential nerve damage or ligamental shifts resulting in subluxation? To what extent (if any) will leukocyte (white blood cell) and erythrocyte (red blood cell) production be affected by the fracture? As it is easy to see, one ostensibly isolated occurrence in one system quickly spiders out to cause changes in many others.

This is especially true of cigarette smoking, such that if one was to accurately amend the title of the previously referenced fictitious article, it would read: Recent Study Finds Cigarette Smoking Directly Linked to COPD, Thereby Inducing a State of Chronic Hypoxia, Which Accelerates the Degradation of Neurological Function, Which in Turn Causes... In short, nowhere on planet Earth is the butterfly effect more apparent than in our own bodies. Literally every micro-event spawns thousands of others, which is why smoking is so radically dangerous.

Things start going south from the very first drag. The first system to be affected is technically (and surprisingly) not the respiratory system, but the digestive. It is well known that cigarettes assault the lungs with a vengeance, but one of the nastiest and least-known effects of tobacco inhalation takes place right under the noses of smokers - literally. As smoke enters the mouth, it significantly raises the temperature within the oral cavity and partially dries out the naturally saliva-covered inner surfaces of the mouth, thereby providing a near-perfect environment for polymicrobial unpleasantries to thrive, often resulting in festering dental abscesses, a common problem amongst smokers of any age group.

Of course, as shows like Dr. Oz and The Doctors have all-too-vividly shown us, some of the most visibly nefarious effects of smoking take place in the lungs. With every single inhalation, a noxious cloud of uncombusted particles burning at 130 degrees is ushered into the lungs, scarring the cilia and destroying alveoli in the process. This is where the butterfly effect really begins to become apparent from a physiological standpoint. Cigarette smoke contains thousands of harmful chemicals, 60 of which are proven carcinogens (Smoking - The Facts 1). As the lungs attempt to do their job of facilitating the gas exchange of oxygen and carbon dioxide in and out of the circulatory system, these deadly chemicals flood into the bloodstream, depriving some of the circulating red blood cells from the oxygen that they were supposed to have picked up. This, in turn, makes the smoker’s blood oxygen levels drop slightly with each successive puff, placing the individual in a state of mild hypoxia (oxygen deprivation) during the entire time that he or she is smoking.

Ironically, despite the pummeling that the pulmonary system is taking during the first few lungfuls of smoke, the smoker is at the same time experiencing the pleasant rush of nicotine as it crosses the blood-brain barrier, providing mental relaxation, sensations of well-being, adrenal stimulation (which makes the individual feel more energetic and “alive”), increased alertness, and other psychological and psychological positive reinforcements.

Nicotine alone is a largely harmless chemical. It elicits a psychoactive response much like that of caffeine, but is exponentially more addictive. Unbeknownst to most, nicotine is actually one of the most addictive substances on the planet, only to be outdone by heroin. It snares smokers faster and more powerfully than crack cocaine or methamphetamine, making smoking one of the hardest habits in the world to give up. Symptomatic withdrawal from nicotine can begin within as little time as a few hours after smoking, causing the smoker to become agitated, depressed, and prone to heart palpitations. In the smoker’s mind, the only solution is another cigarette.

As the SURGEON GENERAL’S WARNING has proclaimed from cigarette packages everywhere, cigarette smoke does indeed contain carbon monoxide. But what exactly are the implications of this? After all, the popular image of carbon monoxide is that of in-home detectors and quiet suicides in closed garages. Given what popular culture has handed us about the gas, it seems that if cigarettes contained enough carbon momoxide to be a problem, smokers would be dropping like flies. In reality, the amount of carbon monoxide is relatively small, especially when compared to the lethal doses that people often picture. One cigarette’s worth of carbon monoxide is certainly not enough to cause harm, but rather it is the cumulative effect of oxygen deprivation caused by the gas that results in fatalities.

Oxygen, as we have discussed, is carried from the lungs throughout the bloodstream by red blood cells. These cells “pick up” the oxygen molecules by attaching them to the hemoglobin within the cell. Oxygen sticks to the hemoglobin, gets carried to its destination, then detaches itself once at the target cell which it then oxygenates. The erythrocyte then picks up the spent CO2 (carbon dioxide) and carries it back to the lungs where the process repeats.The problem with carbon monoxide is that is “sticks” to the hemoglobin of the red blood cells much more easily than oxygen alone. The extra carbon atoms that help comprise the molecule create an incredibly tenacious bond which prevents the carbon monoxide from detaching itself easily. This means that literally trillions of red blood cells can circulate throughout the body for a very long time with the carbon monoxide molecules still attached to them, thereby preventing them from performing their usual function of cell oxygenation. This is especially harmful in respect to the cardiovascular system.

The first place that oxygenated blood goes from the lungs is to the coronary arteries. The coronaries form a network of blood vessels that runs along the surface of the cardiac muscle, ceaselessly providing it with the enormous amount of oxygen that it needs to pump blood. When these arteries feed the myocardial (heart muscle) structures with carbon monoxide-laden blood, the heart is unable to perform at its optimum level. Additionally, the nicotine spoken of earlier also serves to raise the blood pressure in the body by causing vasoconstriction (spasmodic narrowing of the blood vessels), which requires the heart to work even harder in its already weakened state. Together, the increased workload coupled with the lack of fuel combine over time to produce a prematurely-aged and unhealthily stressed heart, causing exercise to be much more difficult, increasing the risk for heart attack and stroke, and putting the heart at risk for cancerous tumors to grow. (The likelihood of tumor growth is increased due to the fact that insufficient oxygenation of the cells comprising the myocardium makes them more likely to incur genetic errors [the cause of cancer] when they divide.)

In addition to vascular damage, the chronic hypertension caused by smoking also results in congestive heart failure, causing the already-elevated risk for cardiac-related death to skyrocket even further. When the blood pressure is high, the cardiac muscle is constantly being forced to generate more pumping force with each atrial and ventricular contraction than normally required. In the form of regular exercise, this is very good for the myocarduim, strengthening it and increasing cardiovascular endurance. On the flip side, when such a level of hyper-normal performance is perpetually required of the heart muscle, the excess stress causes the muscle to enlarge in size, thickening the ventricular walls. This thickening, dubbed cardiomegaly, prevents the muscle from squeezing in on itself to the degree that is required for optimal cardiac output, therefore some of the blood is not ejected from the ventricles with each contraction, crippling cardiac function severely.

In addition to decreased cardiac output, congestive heart failure also engenders a slew of other maladies, one of the most debilitating being that of pulmonary edema. This condition, which occurs when fluid to seeps into the pulmonary bodies (lungs), presents itself in the form of numerous symptoms including labored breathing, coughing up blood, and frequent chest discomfort and tightness (Pulmonary Edema: Symptoms). As if the misery of pulmonary edema wasn’t enough, to make matters worse, smoking also causes a breakdown of the microscopic “air sacs” (alveoli) within the lungs. These alveoli are the mechanisms that facilitate gaseous exchange during respiration. When bombarded by smoke, however, they are damaged and slowly destroyed over time. Thousands of the decimated alveoli will frequently clump together forming areas of useless tissue referred to as blebs. These blebs become sequestered away from the functioning pulmonary tissue leading to a condition called consolidated pulmonary atelectasia, which prevents the lungs from becoming optimally inflated. Over time, this puts the smoker at a much higher risk for developing bronchitis and especially pneumonias.

In addition to all of the nastiness that smoking invites into the cardiopulmonary systems, the smoker’s travails are still far from over. Accompanying the aforementioned infusion of baleful chemical agents into the bloodstream, smoking cigarettes also exponentially increases the proclivity of the blood to form clots, sending through the roof the smoker’s risk of deep vein thrombosis, pulmonary embolism, and stroke.

Cigarette smoking poses not only mortal dangers, but extremely undesirable cosmetic and sexual ones as well. I have often noticed that a great deal of cigarette advertisements seem to insinuate that smoking provides men with such an irresistible sexual appeal that as soon as one lights up, one should justifiably expect droves of winsome members of the female persuasion to rush forward, defenseless to the allure of the tall, dark stranger with the cancer stick. I find this very ironic, given that smoking directly causes erectile dysfunction, with smoking men having an 85% higher incidence of impotence than nonsmokers. (Moyer, MD 90) Studies have also shown that smoking diminishes sexual pleasure and libido; and if a smoker happens to be married, things become even gloomier. Research has shown that smokers have a 53% higher rate of divorce than nonsmokers, especially if their partner does not smoke (Bachman, et. al. 70). And if the marriage is going sour because performance in the boudoir has gone south, then the unbecoming cosmetic ramifications of smoking will only serve to make things worse in this department.

It is often easy to spot a lifelong smoker from across the room simply because of the toll that his or her deadly habit has taken on the dermatological appearance of the individual. Smokers, especially those that have been addicted for many years, are notorious for the poor condition of their skin. On its face, this fails to make much sense; after all, how can smoking damage the skin when it does not directly attack it like UV rays from tanning beds would? The answer comes in the form of a protein called collagen. Collagen performs many functions within the bodies of humans and other mammals, one of which is to provide elasticity to the skin, preventing it from sagging and providing for a youthful, vibrant appearance. Chemicals that enter the bloodstream through smoking promote the breakdown of collagen, resulting in the premature senescence (biological aging due to mitochondrial DNA decay) of skin cells, thereby rendering the skin void of luster and plaguing it with unsightly wrinkles. In women, the breakdown of collagen tends to appear first in the breasts, causing unattractive sagging and loss of fullness in the mastic tissue. In fact, studies have shown smoking to be the number one cause of sagging breasts in the United States (Slideshow: Surprising Ways Smoking Affects Your Looks and Life.)

Cigarette smoke also affects the durability of keratin, the fibrous protein that comprises our hair and nails. Due to this weakening, smokers suffer chronic yellowing of the nails and endure dry, lackluster hair.

As we discussed earlier, tobacco smoking’s detrimental effects on the digestive system don’t stop at the mouth. Smokers experience elevated instances of gastroesophageal reflux disease (heartburn) and also put themselves at risk to develop Chron’s disease, an inflammatory disorder of the intestines that causes severe pain and many times rectal bleeding.

While most people connect cirrhosis (irreversible scarring) of the liver solely to alcoholism, smoking (not surprisingly) can be a causal factor as well; however it can also affect the liver in other negative ways, including altering the rate at and manner through which it metabolizes medications. This physiological perversion of the normal metabolic processes of the hepatic body (liver) can result in drugs not working as effectively as they otherwise could.

Closely related to the liver, both in terms of function and anatomical location, the pancreas is a glandular organ of the digestive and endocrine systems that serves to produce vital hormones and secrete digestive enzymes. Smoking not only impairs these functions, but pancreatic cancer is nearly as high amongst smokers as it is among alcoholics. The precise mechanism(s) behind this are yet to be fully understood by scientists, but the link is nonetheless present.

In fact, all other factors aside, smokers as a population have higher rates of every type of cancer than any other definable group. Smoking cigarettes raises an individuals risk for all types of cancer, but the most common include: lung, kidney, laryngeal, brain, breast, bladder, esophageal, pancreatic, and stomach cancers. Additionally, if a smoker is afflicted with cancer and still continues to smoke, he or she is more likely than a nonsmoking oncological (cancer) patient to experience metastasis (moving from one part of the body to another) of the cancer, this, obviously, increasing the individual’s chance of death.

Even if cigarettes did not produce such monstrous effects in the health of smokers, the nasty habit would still incur numerous other costs - literally. A conservative estimate of the average price of a pack of cigarettes would run about five USD with some wiggle room for taxes. At five dollars per pack at two packs a day, smoking costs one person roughly ten dollars a day, seventy dollars a week, 280 dollars a month, and 3,650 dollars a year. Ten years of such a habit (even without accounting for inflation) would run a smoker just short of forty thousand dollars - an impressive sum. Even at that, none of these figures even begin to factor in the gargantuan healthcare costs incurred from the slew of potential conditions discussed earlier. A 1997 article published in the New England Journal of Medicine presented research that in reference to healthcare costs,

Per capita costs rise sharply with age, increasing almost 10 times from persons 40 to 44 years of age to those 85 to 89 years of age. In each age group, smokers incur higher costs than nonsmokers. The difference varies with the age group, but among 65-to-74-year-olds the costs for smokers are as much as 40 percent higher among men and as much as 25 percent higher among women.

However, the annual cost per capita ignores the differences in longevity between smokers and nonsmokers. These differences are substantial: for smokers, the life expectancies at birth are 69.7 years in men and 75.6 years in women; for nonsmokers, the life expectancies are 77.0 and 81.6 years. This means that many more nonsmokers than smokers live to old age. At age 70, 78 percent of male nonsmokers are still alive, as compared with only 57 percent of smokers (among women, the figures are 86 percent and 75 percent); at age 80, men's survival is 50 percent and 21 percent, respectively (among women, 67 percent and 43 percent) (Barendregt, et. al. 1054).

In light of such findings, it is abundantly clear that if ALL cost-determining factors are taken into account, the cost of smoking is enough to be economically ruinous on its own. Couple that with all of the previously discussed ailments and it seems as if things could not possibly get any worse. But they do.

On top of the physical and financial burdens that smokers bear, the social stigma of cigarette smoking is yet another negative side-effect of the habit. Smoking has been banned from restaurants and other public venues in several states across the nation, to the jubilant applause of nonsmokers. The nonsmoking community has made it clear that smoking is not a welcome element of social expression whatsoever. Smokers must face the fact that by smoking, they elect to alienate themselves from enjoying social experiences with many nonsmokers, given that the vast majority of nonsmokers will not put up with being forced to inhale the noxious fumes emanating from the glowing tips of the coffin nails between the lips of their smoking acquaintances. For the most part it seems that many smokers simply choose to negate this fact.

In reality, smoking is just about the worst thing people can do to their health, short of locking themselves in a cage of ravenous lions after rolling in steak sauce. The well-known effects are horrible enough, but when viewed alongside all of the other, less-known ramifications discussed in this paper, the very idea of smoking should be repulsive. There is no buzz, no high, no nicotine rush that is worth trading one’s life for. The havoc wreaked upon the physical health, financial security, and psyche of smokers is heinous enough to make any person presented with the evidence think twice. It’s said that it’s never too late to quit, but this is only partially true. There is a point of no return, and that is when both sides of the dashes are filled in on the headstone. Mark Twain once said that “Giving up smoking is the easiest thing in the world. I know because I’ve done it so many times.” Deciding to “quit tomorrow” translates to “never.” It is estimated that 1 billion people will meet their demise from smoking-related illnesses by the end of the century (Sharples). If you smoke, don't let yourself become part of that ominous statistic. Today is the day to quit.

Works Cited

Bachman, et al., Smoking, Drinking, and Drug Use in Young Adulthood (Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence

Erlbaum Assoc, Pub, 1997), p 70

Barendregt, M.A., Jan, Luc Bonneux, M.D., and Paul Maas, Ph.D. "The Health Care Costs of

Smoking." New England Journal of Medicine. 337 (1997): 1052-1057. Web. 27 Oct. 2011.

.

Moyer, MD, David. The Tobacco Reference Guide. 1998. 90. Web.

.

"Pulmonary Edema: Symptoms." 07/29/2011. n. pag. Mayo Clinic. Web. 27 Oct

2011.

.

Sharples, Tiffany. "Smoking Will Kill 1 Billion People." TIME Magazine.

02/07/2008: n. page. Web. 25 Oct. 2011.

.

"Slideshow: Surprising Ways Smoking Affects Your Looks and Life." Infographic.

WebMD.com/smoking-cessation. Louise Chang, MD. New York, NY, USA: Web MD, 2011.

Web. 27 Oct 2011.

.

"Smoking – The Facts."National Library of Medicine - National Institute of

Health. National Institute of Health, 07/14/2010. Web. 25 Oct 2011.

.

Similar Articles

JOIN THE DISCUSSION

This article has 0 comments.